What does it mean to “know” a language?

The phrase “knowing a language” is difficult to define. One popular query for anyone looking to learn or teach a language is, “How many languages do you know?” But what exactly does it mean to “know” anything, let alone a language?

What you need to know

There’s no simple answer for this. This is because knowing a language is more than understanding a large vocabulary list. If it were, all you would need to do is memorize a deck of flashcards and then you’d be fluent. Knowing a language is more than understanding how the grammar works. If it were, you could read and study all the grammar rules, as if they were universal, and then be able to communicate. And knowing a language is more than just the very language itself. If it were, there would be no need to understand anything about the history, culture, or people of a given language community.

The reality is knowing a language means some combination of all these aspects and how they relate. So, here’s my list of what you need to know (to some degree) to say you “know a language”.

- Lexical Knowledge (many, many words)

For example: ball, person, they, can

- Morpholexical Knowledge (how new words are created)

For example: redo, truth-iness, underanalyze

- Morphological Knowledge (the different forms words can take)

For example: table or tables, speak or speaking, I or me, let’s or let us

- Grammatical Knowledge (the different kinds of words there are)

For example: noun, adjective, pronoun, verb

- Syntactic Knowledge (how various kinds of words work together)

For example: I’m giving her a ball, what do you think?

- Idiomatic Knowledge (common expressions and their structure)

For example: without further ado, keep an eye on him, you made me do it, a big new comfy black couch

- Pragmatic Knowledge (what is often implied, but not explicitly stated)

For example: guess what?, that taco looks delicious, want to get a cup of coffee?, forceps!

- Discourse Knowledge (the kinds of contexts certain language is used in)

For example: once upon a time, ladies and gentlemen, don’t forgot to hit subscribe

Note that this list doesn’t address how a spoken language can be “performed” in different ways, such as how it can be pronounced, heard, written, read, signed, texted, or similar.

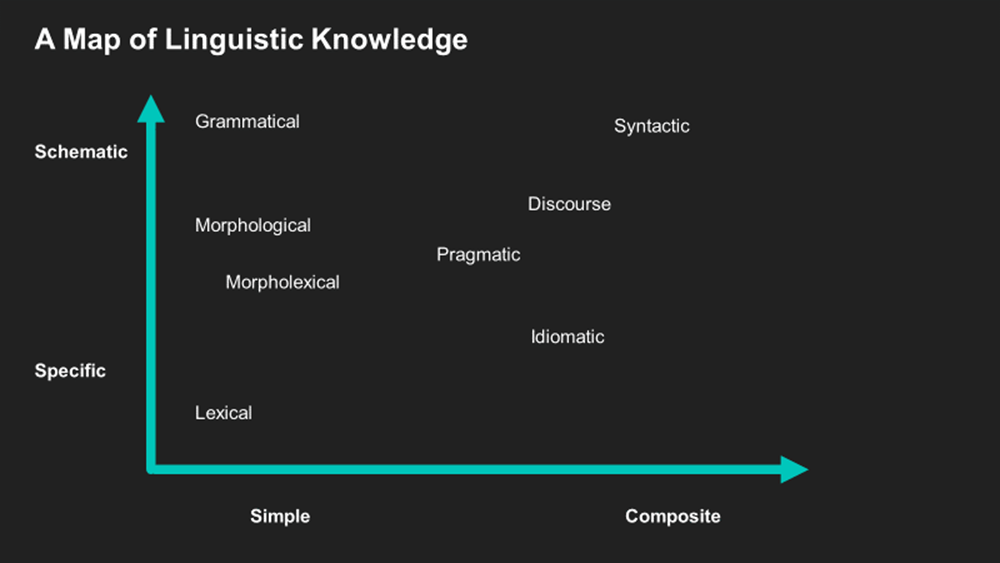

Mapping Linguistic Knowledge

All the types of knowledge mentioned above are also related to each other in certain ways. The following image illustrates this.

Let me explain. We’ll begin with the two axes.

The vertical axis represents a continuum from specific to schematic. “Specific” refers to having a limited or well-defined meaning, and “schematic” refers to having a broader or abstracted meaning.

The horizontal axis represents a continuum from simple to composite, that is having few parts to having many parts. With this in mind, let’s talk through why each kind of language knowledge is positioned where it is.

Lexical

Lexical knowledge refers to the simplest and most specific parts of language, that is, the individual words you find in a dictionary. Technically, the different word entries you find in a dictionary are called “lexemes”. The reason for using this technical term is because many different forms of a “word” can refer to one and the same “word” (= lexeme). For example, in English the “words” (= forms) am, be, was, were, being are all the same “word” (= lexeme). And technically, the specific “word” (= form) that is chosen to represent the lexeme in a dictionary is called the “lemma”. It’s simply convention that determines what the lemma is.

When you begin to learn a language, the primary focus is learning more and more lexemes.

Morpholexical

As you get more schematic (and perhaps slightly more composite), the next kind of knowledge is morpholexical, that is, how words are created.

For example, it’s one thing to know the lexeme “study” (as a verb), but it’s another thing to understand how “study”, “studious”, “study hall”, and the nouns “studies” are related to each other. How you take the “root” -stud and form different words refers to morpholexical knowledge.

Here it’s useful to know what a “morpheme” is. A morpheme is the simplest meaningful “part” of a linguistic expression. For example, look at the word “undeniable”. This word contains the parts un- + deny + -able, which are each called morphemes. The morpheme un- makes something negative and is always bound to other morphemes. The morpheme deny is a lexeme that refers to declaring something to not be so. And the morpheme -able is always bound to other morphemes and refers to an attribute.

As you learn a language, recognizing how different morphemes come together to forms different lexemes is key to quickly acquiring more vocabulary.

Morphological

Very similar to morpholexical, but still distinct, is morphological knowledge. This knowledge refers to the different forms a word can take.

For example, in English you say “she walks” with the form -s, whereas you say “they walk” without the -s. Here “walk” and “walks” are different forms of the same word (= lexeme).

Some languages can be difficult to acquire because they have a very complex system of forms compared to others, and others languages will have very many irregular forms to internalize.

Grammatical

This takes us to grammatical knowledge, which is the most schematic, yet simple kind of language knowledge. Grammatical language here refers to the different types of words a language has.

For example, due to the way our human minds work, it’s universal for languages to have “nouns” that refer to “things”, and “verbs” that refer to processes or relationships. And most languages have words like “and” “but” “or” to link thoughts together, and words like “of” “from” “with” to link certain kinds of words together.

As you learn another language, it’s important to understand the various kinds of words there are, even if you can’t always give it a label.

Idiomatic

If you look at the horizontal axis, the most specific kind of composite knowledge is idiomatic. Like lexemes, so-called “idioms” in a language have a specific, defined meaning, but unlike lexemes they are composite because there are more parts (= morphemes).

When you learn a language it can be difficult to recognize and understand idioms at first because the meaning is not obvious from the sum of the parts. For example, in English the idiom “to kick the bucket” refers to someone dying, which has nothing to do with the action of kicking and nothing to do with things we call buckets.

This unpredictable nature of idioms can make learning a language difficult, especially since many language learning reference sources like dictionaries, grammars, or phrasebooks don’t capture idioms well. Nevertheless, they are very important to master because idioms exist because they are commonly used.

Discourse

As you get more schematic you approach what is called discourse knowledge. This refers to the different contexts that language is used in. As you learn a language, it’s important to keep in mind that certain lexemes and idioms have different meanings in different contexts.

For example, if you hear the phrase “ladies and gentlemen”, it may evoke the beginning of a sporting event. If you hear the phrase “once upon a time” you know you are hearing the beginning of a story. And if you hear someone say “don’t forget to like and subscribe,” what context can you imagine other than a video on Social Media?

So, when you learn a language, it’s important to be aware of the different contexts you are in, because how words and idioms are used in one may vary greatly from another.

Pragmatic

In the middle of the chart we have pragmatic knowledge, which is closely related to discourse knowledge. This refers to how context determines the meaning of language. Many times it refers to meaning that is implied, especially with so-called “incomplete sentences”.

For example, if you hear someone say: “Guess what?” you are not likely being asked to give an answer, but rather prepare to hear some surprising news. Or if a surgeon says “forceps!”, they are most likely asking for an assistant to hand them forceps to perform an operation, even though they are not using a verb.

When learning a language, it’s important to learn with tutors or instructors who make sure you understand what is implied.

Syntactic

As you get more and more schematic there is syntactic knowledge, which is technically called “syntax”. This refers to how different words work together to form more composite units, like phrases and sentences. Admittedly, one might consider this to also be grammatical knowledge, but it’s useful to distinguish the two.

For example, let’s take the example sentence: “David is giving Jeff Mark’s book.” Who’s the person doing the giving? David. Who’s receiving the book? Jeff. Whose book is it? Mark’s. You know this as an English speaker because you have internalized the syntax.

When you are beginning to learn a language it can be difficult to understand the syntax because it is indeed the most composite and schematic aspect of a language. This is why a common beginner’s question is: “Why do you say it this way?” The short answer is “Because that’s how you say it.” And the longer answers tend to be explaining the syntax and concepts like “word order” or “object”.

So, don’t worry about mastering syntax at the beginning of a language learning journey. As you first expose yourself to many words, forms, and types of expressions, you will inherently learn the syntax piece by piece.

Putting it all together

To sum things up, knowing a language can refer to very different kinds of knowledge. And to become truly fluent it’s important to learn each one of them to some degree. Unfortunately, many language learning solutions just don’t work because they might focus on a few areas and do them really well, but they omit others, which leaves gaps in your knowledge.

If you want to learn about how you measure fluency in a language, check out our article here.

To address this “gap” problem Immersio provides all its instructors and tutors, and in turn learners, with a platform that makes sure that every kind of knowledge mentioned above can be addressed. This is why every single lesson of every Immersio course contains a dialog that immerses you in a specific context for the purpose of teaching you specific language skills. This is why every single lesson addresses the dialog’s vocabulary, phrases, and grammar as such so as to directly explain the kinds of simple or composite, and specific or schematic knowledge there is to know. And this is why every single lesson gives you the opportunity to use your knowledge and speak right away with Immy, tutors/instructors, and other co-learners.

Start Speaking Today

Register now at an Immersio site to start speaking whatever language you want to acquire and master this knowledge. Check out the content of each course so you can focus on reaching your specific language learning goals.