Why I Speak Ancient Languages (Personal Post)

Speaking Ancient Languages

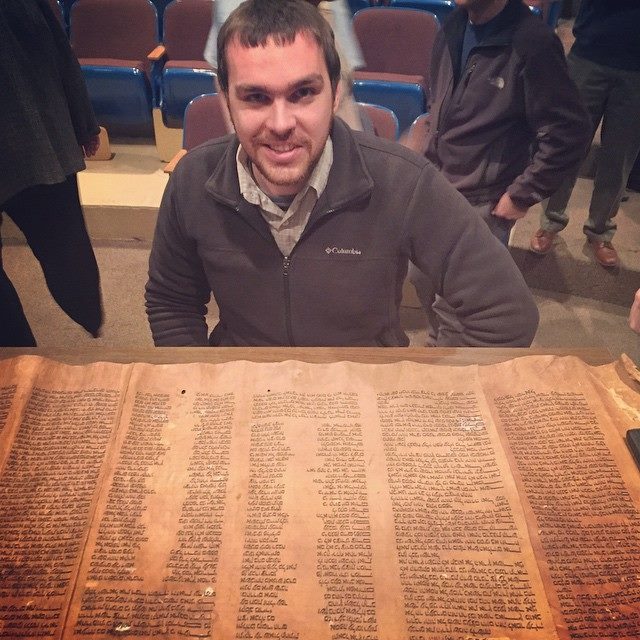

For anyone who knows me (David J. Sigrist) well, I have learned, taught, and, of course, “used” ancient languages for decades. In particular, my personal and academic interests in Graeco-Roman and Jewish history, thought, and texts have led me to become proficient in various older stages of the Aramaic, Greek, Hebrew and Latin tongues (with a cursory knowledge of other related ones…). I’ve even had the opportunity to use my talents to write ancient language spells and scripts for the show Supernatural as a result during its run (this is probably my favourite segment I’ve scripted).

As I observe how ancient languages like these are commonly studied and used, and compare this to my experience learning and teaching modern languages, my experience has thoroughly convinced me that speaking an ancient language from day one leads to

- a more engaging and effective learning experience

- an otherwise unattainable nuanced understanding of the language, and

- vastly greater ease for engaging closely with ancient texts and thoughts.

My experience has also taught me that this notion of speaking ancient languages is not as controversial as some debates would have it appear.

Many instructors in institutions or departments that focus on Biblical Studies or Classical Studies acknowledge the benefits of “communicative” or “living language” approaches over “grammar translation” or “tools based” ones that have become commonplace in the last few centuries.

The friction, as I have encountered it, lies in doubting the feasibility of implementing so-called “living language” approaches themselves, which is something I’ve spoken about many times in scholarly conferences as I advocate for digital solutions. The two main factors then become 1) instructors’ own lack of proficiency (which can admittedly be a source of embarrassment), and 2) the lack of study hours and resources departments will allocate. Fair enough.

In the last few decades this has resulted in many institutions either abandoning “original language” study altogether, or resorting to using “tools based” approaches where learners are trained to use digital tools that can quickly provide lexicon references for individual words, parse words to give basic grammatical information, or link to relevant articles or studies of key passages.

Tools or Grammar Based Approaches

Here I will acknowledge one point with a caveat, perhaps to the chagrin of fellow advocates of speaking ancient languages. For institutions with limited resources who are conducting a cost-benefit analysis of how many hours to dedicate to language instruction amid other pressures, a reasonable decision may be to seize the low-hanging fruit and use “tools based” approaches.

Particularly in Biblical Studies this may be prudent because the corpus that most scholars or professional religious workers are expected to work with are orders of magnitude smaller than even Classical (Graeco-Roman) Studies.

For example, by any count, the Hebrew Bible contains less than 450,000 words, and the Christian New Testament is a fraction of the size. By contrast, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey alone contain roughly 350,000 words, and the Loeb Classical Library (which, for the sake of comparison, can approximate a rough number of ancient and early medieval writings to be included in the Classical Graeco-Roman corpus for study) contains over 500 volumes, each with hundreds of thousands of words or more. And this does not even touch the vast world of Latin and Medieval Greek documents and usages outside of any fixed corpus. Even if one were to “stretch” and include the Babylonian Talmud in Biblical Studies, which is perhaps the largest ancient/early medieval work included in a literary corpus, the number of words is roughly 2 million.

My intuition is that this is at the core of why spoken or “living language” approaches have been relatively slow to gain momentum in Biblical Studies circles, whereas by comparison Living Latin has flourished for more than a generation now and is poised for even greater growth.

However, with this being the case, let me strongly warn that learner expectations must then follow suit. When someone attends a seminary or college, let’s say, where “tools based” or “grammar translation” approaches are used, they should not expect to become independent readers by the end of their studies or to even be on that path. They should not expect to be able to truly say “I know Biblical Greek/Hebrew”. They should not expect to be able to casually read any significant portion of a biblical text without a dictionary and grammar aides. And no one should ever tell an aspiring learner who struggles with these approaches that they don’t have a “mind for languages”, or anything of the sort. And mūtātīs mūtandīs the same is true when such approaches are used in Classical or Medieval Studies departments.

Rather, such learners should know that they are going to be able to more confidently consult academic articles and better follow lines of thought where original languages are used. They should expect to have a solid understanding of “metalanguage” for talking about the original languages (and as an aside not expect to become linguists or proper grammarians because of it). At best they should expect to be able to “work through” key passages that are meaningful to them and have a passing knowledge of core vocabulary and grammatical concepts. Such courses straddle a fine fence between language learning and descriptive linguistics, taking bits of pieces from each as they find it useful for their unique purposes.

To use an analogy very familiar to those who live where I do in the Pacific Northwest, they will be trained on how to understand maps of the terrain of the text, who the most renowned guides are to consult, and where the most well-known vistas may be found. However, they will not be well-equipped to walk the path themselves. For those that do caveat lēctor.

Immersio’s Purpose

Again, for many organizations who follow such approaches and give learners such expectations, this may be fine and good, but they are not mine nor Immersio’s.

Rather, Immersio exists to get any learner on the path to lasting fluency through contextual conversations and meaningful, repeated use of the language(s) they want to learn. Immersio exists to be part of creating a world where “any language can be learned and spoken by anyone”. Immersio exists to provide any learner with what I desperately wish I would’ve had access to earlier in my life. Immersio’s methodology is the result of me and those I have worked with haphazardly taking our machete through the jungle of teaching ourselves to speak an ancient language, mistakes and all, and sharing our findings. And of course the work isn’t finished. But it has begun.

Circling back, for anyone who knows me well, the COVID-19 pandemic greatly negatively affected my ability to contribute to this lifelong mission of mine the last few years. The reality is I am also a husband and father of three littles ones, and I want to treasure my time with them. I am also the sole income earner and a homeowner in what is consistently ranked one of the, if not the, least affordable places to live in North America (but also most liveable and most beautiful). And I have dear friends, relationships, and other hobbies and professional competencies I want to maintain. In short, like you (presumably…) I am human.

Nevertheless, the future looks bright for Immersio. I am eternally grateful to friends, partners, and mentors who understand my vision and are here to help make it a reality. Special and eternal thanks goes to my business partner Winston who shares my passion for education and can manage teams and expectations like no one else. I am indebted to Vancouver’s vibrant entrepreneurship ecosystem, and programs and services offered through the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, which will enable us to take Immersio to the next level.

Especially from the beginning of the pandemic, I’m happy to have formed new friendships and expanded my circles with like-minded leaders and advocates of speaking ancient languages worldwide. And through promising pilots we’re very encouraged to see Immersio’s tools helping to revitalize indigenous languages and cultures as we help others get blended learning done right. So, throughout the coming weeks, months, and years we look forward to not only contributing content more regularly, but also turning our social impact venture into a sustainable and soon to be scalable organization.

Thank you for reading. Join us in our vision, and look forward to more.

Talk soon,

David